Interview with Constance Campbell, a Trainee Solicitor at Winckworth Sherwood LLP

August 11, 2022

Disney Overtakes Netflix in Subscribers

August 16, 2022Article written by Tammy Ho

After 19 days of the strike, the Criminal Bar Association announced a further ballot looking for an escalation of strike action on 8th August.

Criminal Barristers’ strike

Criminal defence barristers have been going on strike on alternating weeks facing underpaid work, if not unpaid. Their actions are organised in a bid to be paid duly for their professional work and to alleviate the current talent drain. Unlike other professions, self-employed criminal barristers lose income while they go on strike. They are unguarded in the process of pressuring the government for an improvement of legal aid policies.

Criminal Barristers’ life

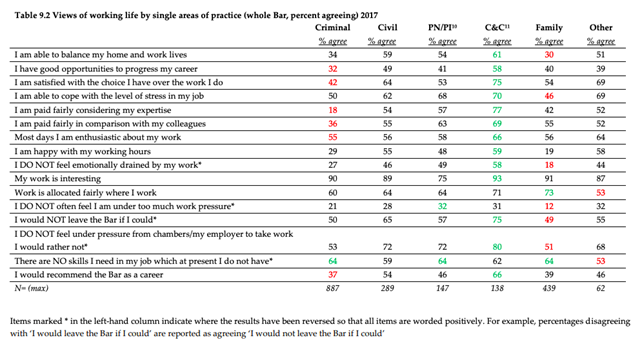

Findings from the Bar Council’s report in 2017 demonstrate why criminal barristers have a particularly difficult life in the seemingly fabulous profession. Career progression, fair remuneration, stress from work and career prospects are the worst in the criminal bar among all practice areas (Figure 1).

Retrieved from Barristers’ Working Lives 2017 available at https://www.barcouncil.org.uk/uploads/assets/694001c1-7e81-4f21-8709602e7d9238ee/working-lives-2017.pdf .

Criminal barristers’ work

57% of criminal barristers work more than 50 hours per week in 2017. More than 20 hours per week are unpaid for 35% of criminal barristers. According to the criminal legal aid programme, the government determines a fixed cost for each case regardless of the working hours, which is only payable after the trial is over. All the hours of preparation are unpaid. These go on while barristers still have to pay for office rent, travelling between courts across the country and accommodations for trials in courts outside their hometown. Regardless of how passionate a junior criminal barrister may be, facing such numbers does not allow one to continue making a living while defending people who cannot afford legal advice.

Government’s reaction

In response, the government has promised a future 15% fee rise, which will not apply to the backlog of 58,000 cases in crown courts. Over the past 25 years, amounts paid for legal aid work have been both frozen and then cut. A 15% fee rise is not adequate to catch up. This pay raise, which will not reach criminal barristers until 2024, is not keeping junior barristers in this profession, some of whom are already in debt.

Criminal barristers work well if the legal aid system performs properly. Many people cannot afford expensive legal advice. If the legal aid system does not pay criminal barristers sufficiently to make ends meet, only the rich could afford legal representation. The poor have to stand on their own feet in courts. Chances are, innocent civilians without legal backgrounds get wrongly convicted.

However, the dooming profession is driving junior barristers out. Figures suggest that nearly 40% of the most junior have to quit. Whereas junior criminal barristers in the first three years of practice typically earn £12,200 per year, an Uber driver working similar hours can earn an average of £26,400 annually deducting car rental expenses. No one expected to gain big money before joining the criminal bar. They aspired to work for the justice system and to live a modest life. But reality strikes that they cannot even support themselves. They do not intend to switch professions. They have to.

Do we need criminals barristers?

Do we need criminal barristers? We need them to achieve a fair outcome in court. Brain drain due to the failed legal aid system would not sustain this profession. Criminal barristers do not earn little because there are too many sharing the cake. Criminal trials become unable to go ahead because there are simply not enough criminal barristers available to prosecute or defend, according to the Criminal Bar Association. We have a shortage of criminal barristers. Only more need to join, and we need to think of how.

What to do?

Unless we want only law graduates from affluent backgrounds who may not have to worry about living expenses and may afford to pour money renting chambers and travelling for work before having earned a minimum wage to join the criminal bar, some policy changes are necessary. On top of an increase in legal aid funding, government subsidies for junior criminal barristers to cover chambers’ rent and inbound work travels may also support the continuation of this profession. The judiciary may also consider the use of remote hearing post-pandemic for selective cases to reduce the expenses and travelling hours of barristers. In the meantime, we shall await the influence of the collective force of the criminal bar.